|

|

An Inevitable Conflict In time, distinct differences deeply divide once close loyalties. Differences rose partially from ideologies among those who first immigrated to north America, but more so from the great minds of men and women destined to come later. The colonists were now deeply cultivated in freedom’s essential habits of self-reliance, integrity, and knowledge of both their temporal and divine purposes. From these storm clouds An Inevitable Conflict arose, bringing about the planting and cultivating of freedom’s seeds. The early emigrants came for a variety of reasons, some for religious freedom, others for opportunity, some against their will, and others plainly because they were destitute. Many who came sought more than mere existence. The famous Puritan minister, John Winthrop, described America in his famed "A Model of Christian Charity" through scripture, "You are the light of the world. A city that is set on a hill cannot be hidden.” “For we must consider that we shall be as a city set upon a hill. The eyes of all people are upon us.” Later, others endowed with unusual  talent shouldered the responsibility broadening, detailing, and molding a prophetic destiny. talent shouldered the responsibility broadening, detailing, and molding a prophetic destiny.President John F. Kennedy once spoke about the truly unique nature of the many great men who later came to lead our nation. At a White House dinner engagement in 1962, he remarked, "I think this is the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge, that has ever been gathered together at the White House, with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone." But to begin, of the many who immigrated, these groups stand out in importance. We begin with the Pilgrims. Many often mistakenly intermix the Pilgrims and Puritans. The two were similar, yet quite different. Religious beliefs directed the Pilgrims westward. As Separatists, they held a strong belief "that membership in the Church of England violated the biblical precepts for true Christians." Scripture "gave urgency to their actions." The Plimoth Planation said in the Geneva translation of Second Corinthians 6: 16-18: (16) And what agreement hathe the Temple of God with idols? for ye are the Temple of the living God: as God hathe said, I will dwell among them, and walk there; and I will be their God, and [they] shall be my people. (17) Wherefore come out from among them, and separate your selves, faith the Lord: and touch none unclean thing, & I will receive you. (18) And I will be a Father unto you, and ye shall be my sons and daughters, saith the Lord almighty. They came with expectations of "building a community patterned after the heavenly city," that God might grant unto them "the salvation of their souls." Many of their practices mirrored necessary attributes for successful free societies. Among their beliefs, they held that a person's character determined their station with God. The congregation elected ministers, elders, and teachers, and held them accountable, much in the same way we elect and attempt to hold accountable governmental officers. Each local area organized its own church accountable only to God. They strongly practiced a separation "between church and state" and for that matter a separation between themselves and all other religions, though their Governor did lead his people to church. Meeting houses were very simple, consisting of pews and a pulpit. They meet twice on Sunday each time for three hours. Attendance was mandatory, but membership usually came by a simple profession of faith. Prayer was extemporaneous. The Pilgrims survived, at least in part, because of unexplainable experiences, which they openly attributed to the grace and hand of God. One came during the summer of 1623. After finally solving issues gravely affecting their industriousness, a sever summer drought collapsed upon them. The anguished colonists watched the fruits of their labor wither; fully expecting to starve. In July, Governor Bradford called for a day of community fasting and prayer and all willingly took part. The next morning, rain began and continued for two weeks of which the governor later wrote: "Such softe, sweet and moderate showers…it was hard to say whether our withered corn or drooping affections were most quickened and revived." Founded in England, after testing the waters of other counties, the group fully understood that it couldn't stay in Holland. They sent representatives, John Carver and Robert Cushman, to London to locate investors, willing financiers, for their relocating to the New World. They were specifically instructed not to "exceed the bounds of your commission" and "entangle yourselves and us in any such unreasonable [conditions as that] the merchants should have the half of men's houses and lands at the dividend." The Jamestown failure left investors leery. Finally, without choice and to the dismay of the group, Cushman and Carver signed an agreement with a group led by Thomas Weston. This document contained several unconscionable terms, among the terms was communal ownership and a 50% property tax at the end of the seven-year period. Of the agreement, Tom Bethell wrote, "It is worth emphasizing all this because it is sometimes said that the Pilgrims in Massachusetts established a colony with common property in emulation of the early Christians. Not so." They were forced into it. This was, perhaps the most important outcome at Plimoth (Plymouth), the failed experiment with communal ownership. This policy, which was forced upon them, slammed against the realities argued by Jean Bodin in his “Six Books of a Commonweale.” Bodin purported that communal property was “the mother of contention and discord” and that “nothing can be public where nothing is private.” The hardship of the first two years in Plimoth wore thin upon what were good and Godly people. Not enough to eat resulted from the common ownership of property. Bethell continues, "Bradford reports that the community was afflicted by an unwillingness to work, by confusion and discontent, by a loss of mutual respect, and by a prevailing sense of slavery and injustice. And  this among "godly and sober men." In short, the experiment failed, endangering the continual existence of the colony. this among "godly and sober men." In short, the experiment failed, endangering the continual existence of the colony. By the winter of 1622 and 1623, Governor Bradford met with his council. Bradford later wrote, "At length, after much debate of things, the Governor (with the advice of the chiefest amongst them) gave way that they should set corn every man for his own particular, and in that regard trust to themselves; in all other things to go in the general way as before. And so assigned to every family a parcel of land, according to the proportion of their number." And this they did to "very good success." In time the community prospered greatly. Later, Bradford reflected that their experience confirmed Bodin's judgment. By experience often bitter, the Pilgrims left with us a powerful culture driven by locally controlled governments, elected, and held accountable by citizens; private ownership of properties; and a trust in Devine leadership. One step at a time, a people, a nation was preparing to embrace freedom. The Pilgrims also taught the value of gratitude when giving thanks even with suffering through hardships and periods of death. Like others, the Puritans disagreed with much of Europe's established religion, especially the Church of England, on doctrinal matters. Most sects were strict Calvinists. By the early 17th Century, Puritans across England found with persecution growing a need for a new home. With the Pilgrims successfully immigrating in 1620, a much larger group of Puritans started emigrating beginning in 1630 lead by John Winthrop. Over the next two decades, 21,000 came making them the most populist and influential group in Massachusetts.

More religious groups followed induced from tolerance. Among those who came were Quakers, Mennonites, and Amish and of course others. (The Quakers) Quoted from the Quaker website, “the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) are a movement within Christianity that began in 1650s England. Early Quaker co-founders were George Fox and Margaret Fell (who would years later get married) along with many other Christian dissenters and preachers like Elizabeth Hooton, Isaac and Mary Peninton, Thomas Ellwood, James Nayler, Richard Farnsworth, and many others.” Believing that established religion had become too entangled with government, its early leaders refused to pay tithing or participate in other entangled matters. The followers focused on improving the internal refraining from the external matters. Because of these beliefs, persecution in Europe forced members to look elsewhere. Several different sects appeared in time, some conservative while others are more liberal, but four factors join all groups together, direct access to God, nurturing the life of the spirit in worship, practicing discernment as a community, and living out our faith. In the early times, Mary Fisher and Ann Austin, the first to arrive in Massachusetts, came in 1656 living among the Puritans. Their stay was short being persecuted while in Boston. By 1681, William Penn, who was born in England, but converted to the Quaker faith, arrived in the Colonies in 1682. His background coming from a family of influence in England allowed him access to King Charles II. In time, he worked to settle his father’s estate with the King, which settlement included land west of the Delaware being named after his father, Penn and Sylvania or Pennsylvania. William’s belief has had lasting effects on the American experiment. A few noted from Quakers of the World include “that if people had freedom, education and equal rights under moral laws that they themselves had helped to make, things might go wrong from time to time, but would put themselves right.” Penn through his friendships with Kings managed to influence rights of religious freedom. Pennsylvania would become one of the great colonies and states or commonwealths. An interesting side note follows Pennsylvania’s history. The King gave Penn direct control of the Commonwealth through proprietary colony. In this type of government, the people elected the legislature, the proprietaries appointed the governor. The Governor possessed the power to veto actions from Legislature. By the middle of the 1700’s, within the life of Benjamin Franklin, the proprietor Thomas Penn, son of William, played a lead role. On Franklin’s first official visit to England representing the people of Pennsylvania, he argued with Thomas primarily over the proprietor’s policy of exempting their land, an unfair practice, from taxation. To describe their relationship after these discussions as cordial would misrepresent it. Franklin later confirmed that the difficult relationship further deteriorated upon their meeting. Thomas was not his father, who fostered the “holy experiment,” but rather his own personal wealth. The Anabaptist groups, or rebaptists, were primarily influenced by the teachings and writings of Menno Simons. In his teachings, he commonly uses a scripture, “First Corinthians 3:11: “For no man can lay a foundation other than the one which is laid, which is Jesus Christ.”” Followers of Simons, the Mennonites, broke from other Christian religions in beliefs on infant baptism. Believing this to be an abomination, they baptism their members in their adulthood. About the life of a true follower, Menno wrote, “For true evangelical faith is of such a nature that it cannot lie dormant; but manifests itself in all righteousness and works of love; it dies unto flesh and blood; destroys all forbidden lusts and desires; cordially seeks, serves and fears God; clothes the naked; feeds the hungry; consoles the afflicted; shelters the miserable; aids and consoles all the oppressed; returns good for evil; serves those that injure it; prays for those that persecute it; teaches, admonishes and reproves with the Word of the Lord; seeks that which is lost; binds up that which is wounded; heals that which is diseased and saves that which is sound. The persecution, suffering and anxiety which befalls it for the sake of the truth of the Lord, is to it a glorious joy and consolation.” The Anabaptize movement in Europe grew over time but was constantly being persecuted by others. Thousands were killed for their "heretic beliefs," particularly about baptism. The Mennonites came to America in 1683 because of an invitation from William Penn and settled in what is now Pennsylvania. Later larger groups of Mennonites came in the early eighteenth century, being part of a group of 100,000 immigrating Germans. In early America, they supported the separation of church and state, and were strongly opposed to slavery. Their beliefs included hard work, giving, and strong families have over time left positive influences in American society.  The Amish, like the Mennonites, were Anabaptize, their roots coming from the original Mennonite movement. In the late 17th Century, a convert, Jakob Ammann, revitalized the Swiss French Anabaptize movement proposing twice a year communion and several other practices to closer follow their understanding of the New Testament. He added an approach of strict discipline including excommunication. This last change resulted in a doctrinal wedge between other Anabaptizes (The Mennonites). The Amish, followers of Ammann, became a distinctive cousin. The Amish, like the Mennonites, were Anabaptize, their roots coming from the original Mennonite movement. In the late 17th Century, a convert, Jakob Ammann, revitalized the Swiss French Anabaptize movement proposing twice a year communion and several other practices to closer follow their understanding of the New Testament. He added an approach of strict discipline including excommunication. This last change resulted in a doctrinal wedge between other Anabaptizes (The Mennonites). The Amish, followers of Ammann, became a distinctive cousin. Thousands of Amish were put to death in Europe often by cruel means in the 16th and 17th centuries. Being promised religious freedom and tolerance by William Penn in Pennsylvania, the first group emigrated from Europe between 1720 and 1730 driven by this persecution. Today, they are found in many states and are growing rapidly in numbers. The Amish are a simple people possessing and living by many qualities necessary for a free people: able to forgive; foster humility, self-reliance, service, and patience.

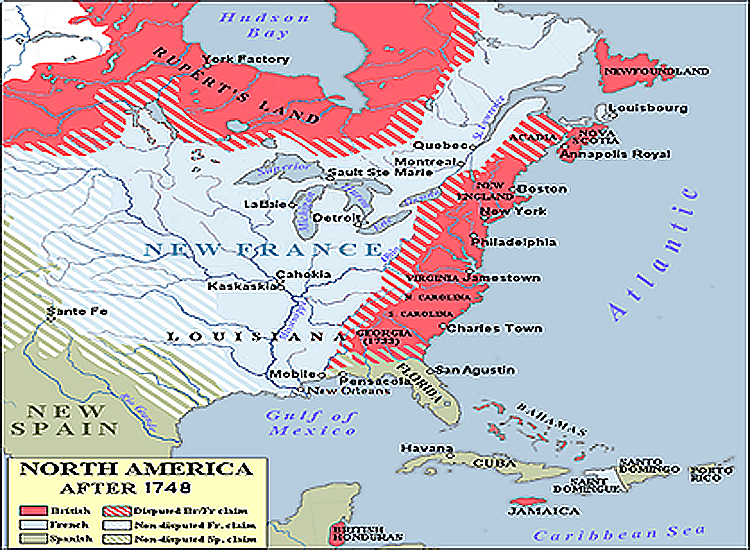

Freedom requires a society of morality something religions sought to instill within its parishioners. The Colonies grew in population reaching a million by 1750. Most were farmers. The rocky lands in the north often drove them to harvest timber and tar for export. The barley, oats and wheat had little export value already plentiful in England. The middle colonies produced corn, wheat, and cattle for export to the West Indies via New York or Philadelphia. Virginia, the Carolina's, and Georgia grew the lucrative cash crop, tobacco. Other southern crops included indigo, flax, and rice. Port cities sprang up: Boston, Salem, Philadelphia, New York, and Baltimore. By the 1760's, their average standard of living became the highest in the world. The riches helped significantly increase life expectancy, having plenty of food and access to the latest in medicines and technology. Adults who survived early childhood lived to an average of sixty-three years old. Twenty-five percent of the population was slaves, mostly in the south owned by the large plantation farmers. The slave market focused on males. Local competition with southern American countries induced the colonies to import women and encouraged the creation of families and children. The Colonist learned to produce what England could not and import their surplus. For many years, the relationship flourished, both sides happy. After the arrivals in the early to mid-1600, the wars endured by the colonists primarily were about land disputes with the French. An extremely critical war, the King Phillip War, was not. Fought primarily from 1675-1676, the war determined ownership and control of New England. After the conflict, a once vast population of Natives now representing only 10% of the total inhabitants was forced to accept foreign control of the land. In 1675, King Phillip, the second son of Massasoit, gathered support from several other Native tribes seeking to destroy the foreigners. A long history of tense relationships between the Natives and the newcomers had finally come to the boiling point. Both sides mistrusted each other, a mistrust stemming from land encroachments and expansion by the prospering English, while the Native population declined primarily from the "European diseases." With respect to population, the war destroyed and killed the largest percentage of population in American history. Thousands of Europeans and over 3000 Natives were killed in the hundreds of battles ranging from Connecticut into today's Maine. The war ended with Metacom's, King Phillip, death during the summer of 1676. Ironically, the son of "the same Massasoit who had helped the Plymouth Pilgrims survive their first winter in the New World" found "[a] father's kindness would become a son's curse." The English and French fought major wars, the King William War 1689-97, Queen Ann's War 1702-13, Father Rales War 1722-25, King Georges War 1744-48, and finally The French and Indian War 1754-63.  British Economic Policy Believing they could catch the Dutch economic power; the English Parliament enacted several policies between 1660 and 1700. The first, Navigation Act, required that all Colony trade had to be shipped with English crews and ships. Certain enumerated goods, sugar, rice, tobacco, and indigo had to go to English ports and were subject to a duty. Direct trade with the Dutch was prohibited. In 1696, the laws were to be enforced in the colonies only in special courts set up by the English with English judges. Over the next several decades, several more laws were added; importing wool band in 1699; hats could not be exported in 1732; no importing of non-British molasses; American could build iron mills after 1750; and limits on free trade of tobacco crippling the Chesapeake. England became wealthy and the contrived laws were designed to do so. For example, prohibiting the exports of Colony hats protected the hat makers of England. The wealth accumulated by the English through their trade practices with the Colonist provided the means for building the all-powerful English navy. Ironically, the Americans would face the brunt of that force in their fight for independence. Generally, the colonies began holding charters of types which freed them from direct involvement with the Crown. The several types of charters: proprietary, royal, joint stock, or covenant. A proprietary charter granted full rights of self-government. Examples include Maryland and Pennsylvania. Royal colonies were ruled directly by the Crown. Corporations managed joint stock. Examples included Plimoth and Jamestown. In 1660 only one Colony, Virginia, was a royal charter. By 1685, only three non-royal colonies were left. England enforced more central control believing central government could better control. Most colonies had a royal governor with a colonial Assembles which in time began to fight over solutions to taxation, roles and power. Even with the ownership changing, England practiced salutary neglect enforcing only the worse cases. This policy began in 1660 with the first Navigation Law and ended near 1750 with the French and Indian War. As long as the money flowed, the mother land happily ignored most violations. The war changed England's policy expecting the Americans to pay for their protection. One writer put it, "colonial discontent soared." Often thunder and lightning warn of the veracity of the coming storm. So, it was with An Inevitable Conflict. Decades long British economic policy, mercantilism, forced American merchants and businesses into selling their goods only to English merchants leaving out of the much more lucrative Dutch trading markets. Although Colonists were offered easy access to loans at very high interest rates, they were often unable to pay back the loans due to the low prices created from the forced British monopolies. In 1760, Washington wrote of his own experience, "I cannot forbear ushering in a complaint of the exorbitant prices of my goods this year. . . . [goods] are mean in quality but not in price. . "

Before 1774, the alarmed Colonists had begun their protests through boycotts and harassment of the Regulars. The Boston Massacre with five Colonists killed begin from harassment. John Adams successfully defended the Regulars involved from an unjust verdict. In 1773, while protesting the tax on imported British tea, patriots dumped 90,000 pounds of tea into Boston Harbor resulting a significant monetary loss. Prior to the party, the citizens of Boston sought permission from the Governor to send the ships in the harbor back to England. The Governor's final decision being no placed in motions the deed. A group of true patriots, the Sons of Liberty, executed their previous determined actions that night dumping tea into the harbor. Of all the lame and unfair laws imposed upon the colonies, one legally dubbed general warrants or general writs of assistance brought more resistance from the colonists than the rest. Historians believe it was this action from Britain that stoked the flames of revolution more than any other. A general warrant contained the power for custom agents to search and seizure without warning and probable cause. These powers came from the Navigation Act passed in the later part of the 1600's. Up until the 1760's, Britain ignored their existence. But with colonist smuggling rampant incentivize by Britain's unfairness with the colonies over taxation, the foreign rulers begin enforcement further driving wedges between the two. A general warrant issued by the King lasted for the King's entire life. Remember King George was the third longest ruler in British history. It empowered the custom agents to search and seize any place, any time ever without probable cause. The basis for our 4th Amendment came from the wretched practice. In Virginia, the House of Burgesses, in response to the Townshend Act, passed resolutions against taxation without representation were made unconstitutional after which, the Governor Botetourt promptly dissolved the body. On the following day, George Washington with others met in the Apollo Room of the Raleigh Tavern to complete it protest. Relations between the Colonists and British in Boston deteriorated further with Thomas Gage’s rule beginning in 1774. The hard-liner Governor viciously enforced laws including the Coercive Act known by the American colonists as Intolerable. This hardline approach existed in four parts, Boston Port Act, closing the port until the losses for the tea was paid, Massachusetts Government Act, a revoking of local government, Administration of Justice Act, colonists not permitted to try British officials, and the Quartering Act allowing the British powers to decide where to quarter its troops. All four laws were targeted at Massachusetts. The American colonists recoiled with sympathy toward Massachusetts. By April of 1775, Gage’s espionage found that the colonists were storing weapons near Concord. Gage sent troops on the evening of April 18th charged with destroying the stash of weapons. 700 Regulars cross the Charles River that night marching to Concord. Paul Revere and Williams Dawes left Boston, Revere by water and Dawes by land. Their purpose was to alert the Minutemen bringing them to battle. Revere had instructed a member of the North Church  to place one lantern if by land and two if by sea. On the night two lanterns appeared. After alerting the militia respectively along the separate routes, Revere and Dawes rejoined at Lexington. Deciding to continue to Concord, Dr Samuel Prescott, a fellow patriot joined the two. A brief time later, British patrols cornered the three. The patrol captured Revere and detained him. The other two continued warning the towns along the way. to place one lantern if by land and two if by sea. On the night two lanterns appeared. After alerting the militia respectively along the separate routes, Revere and Dawes rejoined at Lexington. Deciding to continue to Concord, Dr Samuel Prescott, a fellow patriot joined the two. A brief time later, British patrols cornered the three. The patrol captured Revere and detained him. The other two continued warning the towns along the way. The Regulars reached Lexington at 5:00 AM encountering 70 militia under the command of John Parker. When the Regulars rush at the militia, Parker orders his men to disperse. Shots were fired by whom is in dispute after which, the Regulars fire killing seven. Immediately, the Regular disengage and march toward Concord arriving at approximately 8:00 AM. The British inadvertently burn a portion of the town. Approximately 200 soldiers advance to the North Bridge of the Concord River to secure that area before advancing upon the suspected site with the weapons. Seeing the smoke from the city while erroneously thinking that the British are burning, 400 militia under the command of Capt. Isaac Davis order the troops to advance. The Regulars had marched across the North Bridge onto the west side of the river when they saw a much larger and disciplined enemy march towards them. Immediately, they recrossed to the eastside posturing for defense. When within range, the Regulars shot killing Davis and one other patriot. What happened next changed history. From American Battle Field Trust, “Major Buttrick of Concord shouts, “For God’s sake, fire!” and the Minute Men respond, killing three British soldiers and wounding nine others. This volley is considered “the shot heard round the world” and sends the British troops retreating back to town.” It was the first time an authorized American military leader ordered fire upon their British enemy. Those shots hit and killed or wounded several Regulars. Ordered to retreat, the British went south and then west on what would become known as Battle Road. The Minutemen came, being summoned by a prearranged warning system. With the day progressing, over four thousand Minutemen joined against 1700 Regulars. Minutemen from behind trees and rocks shot the retreating enemy for close to 16 miles killing 73 and wounding approximately 200 more. Within days, Gage, in Boston, found himself in dire circumstances facing 20,000 patriots along the north side of the Charles River. During the early 1770's, relations between the Motherland and the Colonies had degraded severely forcing great thinkers to consider a path forward for the Americas. By early 1773, Jefferson accompanied by a four of his colleagues initiated a direction which in time lead to the "formation of the First Continental Congress." That group included Patrick Henry, Richard Henry Lee, Francis L. Lee, and Dabney Carr. With the Governor continuing to dissolve the Assembly, the House continued to meet privately. In Virginia, the belief that an attack on one colony was attack on the whole found firm footing. With a resolution against the tyranny inflicted by the British upon the colonies passed, the House sent copies to all other colonies for consideration. In May of 1774, Jefferson proposed a day of fasting for His support. Once again, the Governor dissolved the House, which promptly meet at the Raleigh Tavern. Included in that resolution for a day of fasting was the charge for the counties of Virginia to meet and consider sending delegates to a general Congress to be held in Philadelphia on the 5th of September. At the Virginia meeting, Jefferson brought a self-written document, A Summary View of the Rights of British America with him. Though not accepted by the general gathering, its clear tone and thoughtful message was sent by the Virginian legislature to all the colonies. It begins, "Kings are the servants, not the proprietors, of the people." The general Congress first meet in September of 1774. Its first order of business concerned embargos against British imports and exports. Although the Congress failed in passing legislation, it sent its thoughts on trade to the English Parliament. The group also set a time for future meeting in the summer of 1775. On May 10 of 1775, the Congress meet and continued to do so through 1781. Jefferson returned home in early 1776 to be with his family. Some sickness and family death held Thomas at Monticello until May after which he returned. On June 7, Richard Henry Lee, fellow delegate introduced his resolution, "Resolved, that these united colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent states…" The general assembly choose a sub-committee of five with whom Jefferson was a part. Primarily through the influence of John Adams, Jefferson became the pen of that precious document, "The Declaration of Independence." Much modern-day discussion about Jefferson and slavery clouds his real beliefs. Jefferson tried and failed at least once to abolish slavery in Virginia. With slavery the law, he had no power to free them without risk that others would re-enslave them. The author of American Stories is not aware of writings or documents that effectively argue otherwise. We will have more to write on this subject later in the detailed discussion of the Declaration. On July 2nd, 1776, Congress passed Henry's resolution followed by two more days of discussion and arguing over the final wording of Jefferson's draft. On July 4th, Congress passed the Declaration of Independence. The citizens were no longer colonists, but now Americans, citizens of the United States of America. It' critical to understand that this document and the Constitution charged states not the Federal Government with the primary role of governance. It is not centered on Washington, rather that Washington gained its powers and authority primarily through the states with underlying help from citizens. The Colonists and British enjoyed a peaceful and beneficial relationship during the 17th century. The Colonists raised valuable crops, harvested natural resources, and exported these to England. The English by mandate forced their manufactured products back to the Americas. Yet it worked. During the 17th and early 18th centuries, the American culture changed. Self-government fostered from the lowest levels rather than the English's central approach, especially in New England and Virginia, developed. The governance found in the Anglican and Puritan churches, and the self-governing ideals organized in Jamestown successfully spread and brought order and a relative amount of unity among the governed. The variety of religious practices brought balance and encouraged tolerance. Many immigrates had come seeking the privileges of religious freedom. Others, such as the Pilgrims, came because the "Spirit constrained them." Still others came seeking to create their vision of the true order of heaven practiced by the New Testament Saints. A constant flow, of timely experiences difficult to explain even through our modern understanding of science, cemented their beliefs that divine providence protected and guided their way. But the peaceful co-existence shattered when the British usurped colonial practiced autonomy. Separation, success, and natural differences had induced sovereignty in the colonies. Parliament's willingness to break her-own rules and pass taxation without representation left military conflict as the sole means of resolution. The colonists clearly understood the significant amount of power being transferred to the English by these actions. Considering that this taxation was an added burden to an already 50% British take through the mercantile system, enough was enough. The long-term success of the colonist's decision rested solely upon principles. Among the societal beliefs and practices were self-education, self- reliance, charity, integrity, and reverence for their maker, all being critical attributes in their understanding of the sought after "Heavenly society." They educated themselves. With over 90% of the population schooled sufficiently for their primarily profession as farmers and small business owners, the colonies were well prepared to decide upon and undertake its own path. Although far from perfect, their basic understanding and practice of self-reliance, integrity, Godly reverence, and charity opened the flood gates for Heaven's help and did it come, yes in full force. During the following decades, a free nation came forth with power to bless all. |