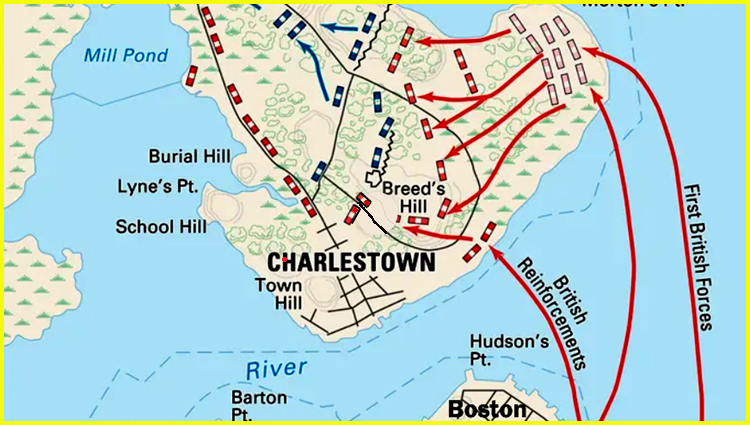

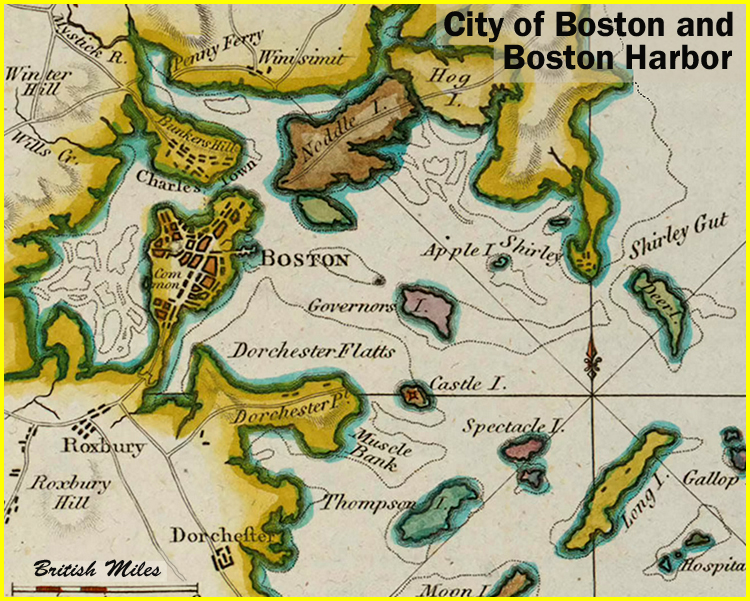

1775-1778: The Critical Years Part I [Go to Part II] The Early British Strategy During the 1760’s, patriots in Boston rejected, with an element of force and passion, the newly passed taxation laws enacted by Parliament. By the late 1760’s, unrest provoked England into sending first a war ship and then troops to restore order. Boston and the surrounding area had become an organized region of rebellion in the eyes of the King. When the British Regulars marched to Lexington on April 18th, 1775, thirteen British regiments (a large number) and several warships were in Boston. Between the springs of 1775 and 1776, the Continental troops were under the command of several leaders yet managed to pin down the Regulars. While the Colonists were modestly successful in Boston, a critical battle fought at Quebec in December of 1775 turned disastrous. At the Battle of Quebec, the Army under the command of Richard Montgomery and Benedict Arnold suffered a swift defeat. Montgomery died during the fight and much of Arnold troops were captured including Daniel Morgan. For the balance of the winter, Arnold attempted to lay siege upon Quebec without success. In May of 76, the British, with newly arrived reinforcements, routed the Continentals forcing them into a disorganized retreat. The failures of the Colonist’s in Quebec and their modest successes in Boston set the stage for war. The British plan was to split the rebels, English General Burgoyne leading from the North and General Howe from New York would isolate rebellious New England. The British planned to enforce the complete isolation of New England with their Navy positioned around the northern American ports. Their belief was that splitting the Colonies meant destruction. (Breed’s Hill)  American Battlefield Trust wrote, “The American patriots were defeated at the Battle of Bunker Hill, but they proved they could hold their own against the superior British Army. The fierce fight confirmed that any reconciliation between England and her American colonies was no longer possible.” After the Breed's Hill Battle, the rebels maintained their position on the northside of the Charles with the British Regulars in Boston through the summer, fall and winter. Washington arrived triumphally to assume his role. Several times, Washington proposed to the war council his desire to attack Boston forcing the enemy into retreat. Almost unanimously, the council rejected reasoning that among other things, their circumstance of extreme military supply shortages prevented it. Occupation of a small jut of land south and east of Boston known as Dorchester Heights decided the Boston campaign. Both sides understood its importance. The Brits needed it to protect. The Colonist’s occupation left Howe’s forces open to destruction by cannon. Major General Henry Clinton wrote, “I foresaw the consequence, . . .that if the King’s troops should be ever driven from Boston, it would be by rebel batteries raised on those heights.”  During the winter, Henry Knox miraculously delivered cannon from Fort Ticonderoga into the Boston area, an act that defied all reality. With additional artillery, Washington now had his badly increased supply of weapons to affectively occupy the Heights. One of Washington’s desires was that the cannon at Dorchester would draw the Regulars out from Boston allowing for an attack from the north on a weakened Boston defense. The war council met finalizing plans to quietly build defenses and move cannon onto the Heights in an unthinkable one night, March 5th, the anniversary of the Boston Massacre. Beginning on Saturday night the 2nd of March, cannons on the north began the planned all night cannonade. Its purpose, create noise and distraction for the troop and equipment movements onto Dorchester. The cannonade continues Sunday and Monday nights, Monday was the crucial night with troops setting up the defenses and cannon on the jutting. With Monday’s open fire, 2000 troops, wagons, guns from Ticonderoga and work crews hidden behind a long row of hay bundles placed during earlier nights, moved onto the steep slopes. “The night was unseasonably mild . . ideal conditions for the work as if the hand of the Almighty were directing things,” wrote David McCullough piecing together thoughts from the many records of the day. Reverend William Gordan wrote, “It was hazy below so that our people could not be seen, though it was a bright moonlight night above on the hills.” The rebels toiled relentlessly during the night finishing by daylight. Reportedly General Howe exclaimed, “My God, these fellows have done more work in one night than I could make my army do in three months.” Although attempts were made, the British cannon couldn’t elevate to strike at the enemy. Washington came on the 5th to inspect and reminded his troops of the important anniversary date. At noon, the British began its infantry strike on the Heights. By early afternoon, the weather took over beginning with strong headwinds, followed by hail, snow and sleet with the onset of evening. The winds turned into hurricane forces describe by Isaac Bangs, the worse storm “ever I was exposed to.” The British counterattack ended during the night having never reached the Dorchester. General Heath of Massachusetts noted “kind heaven” stepped in and intervened. The turbulent weather continued on the 5th through the 6th after which General Howe, feeling that the extra time granted the enemy changed his plans writing, “I could promise myself little success by attacking them under all the disadvantages . . .. wherefore . . .it most advisable to prepare for the evacuation of the town.” Weather miracles aided the Colonists twice at Dorchester, once covering the advances, once protecting the troops from British attack. The war, this war, with its expansive timeline, produced many future miracles. But, unlike this and a few others, the miracles offered paths of escape, rarely if ever, relief from the terrible physical suffering. Although fictional, the story of Rocky, is truly an American story and in the last movie provides a graphic description of what Washington and his armies would soon endure. To his son in Rocky Balboa, Rocky instructs, “Let me tell you something you already know. The world ain’t all sunshine and rainbows. It’s a very mean and nasty place and I don’t care how tough you are it will beat you to your knees and keep you there permanently if you let it. You, me, or nobody is gonna hit as hard as life. But it ain’t about how hard ya hit. It’s about how hard you can get hit and keep moving forward. How much you can take and keep moving forward. That’s how winning is done!” In short order, Washington’s plan morphed from attack into surviving to fight another day. Hardships came often, suffering extreme cold, suffocating heat, starvation and the deep bone chilling from sleet and cold rains. Often, they walked without shoes or badly needed cover. Firsthand, the Americans experienced Rocky’s description. The Continental Congress met in May of 1775 to discuss urgent matters. Among their business was the election of a chief military officer. On the 15th of June, George Washington was unanimously elected General and Commander in Chief for the cause. A tall order sat in front of the General. Within a matter of few weeks, he must put together the entire structure for a national army. Knowing the importance of speedily meeting his troops, Washington left before all the business was concluded. By the 25th of June, Washington and his cavalcade reach New York City where they were welcomed in grand fashion. It was on Sunday the 26th that Washington first received reports from the Battle of Bunker (Breed’s) Hill. On Monday, Washington agreed to meet William Morris and Isaac Low two members of the Provincial Congress. The members addressed Washington supportively of the cause yet diplomatically and without offence respecting “those who feared military rule in America.” Washington simply answered, “When we assumed the soldier, we did not lay aside the citizen,” a statement that over time defined the General. The cavalcade reached Springfield on June 30. Arrangements were made with the gentlemen of the towns along the Cambridge road for escorting the Commander. On the 3rd of July, Washington reached Cambridge and took command. Astonished by what he found, he began immediately shoring up their defenses, while dealing with the many ego driven disappointments among leaders as they learned their new roles and ranks. Now fully in charge. the General worked toward building an army and waited for the British to make their move. He had a threefold issue waiting him, developing discipline among the troops, finding supplies in particular military ordinance, and increasing the numbers. With much effort between July of 1775 and March of 1776, the Continentals pinned the British in Boston eventually forcing their evacuation on March 15. Of the experience in Boston, Washington wrote, “I believe I may with great truth affirm that no man perhaps since the first institution of armies ever commanded one under more difficult circumstance than I have done.” While in Cambridge, the General’s personality and character impressed favorability the citizens. Henry Knox told his wife, “General Washington fills his place with vast ease and dignity and dispenses happiness around him.” Abigail Adams described him, “You had prepared me to entertain a favorable opinion of General Washington, but I thought the half was not told me. Dignity with ease and complacency, the gentleman and soldier, look agreeably blended in him. Modesty marks every line and feature of his face.” The army Washington inherited wasn’t exactly in pristine fighting condition. Without a formal name, the band of rebels were referred to as army, New England army, of the United Colonies, or by the British, “rabble in arms.” But these were not soft common men and women, rather inexperienced. The Pulitzer Prize winning author, David McCullough, in 1776, described, “It was an army of men accustomed to hard work, hardworking the common lot. They were familiar with adversity and making do in a harsh climate, Resourceful, handy with tool, they could drive a yoke of oxen or “hove up” a stump or tie a proper know as readily as butcher a hog or mend a pair of shoes. They knew, from experience . . . the hardships . . . of life. Preparing for the worst was second nature. Rare was the man who had never seen someone die.” Hardy men, that many still would find in the coming army experiences, intolerable. By October of 1775, the Washington and General Charles Lee realized that eventually the British would head to New York City with the intent to severer New England. New York leaned heavily loyalist. Two-thirds of the property was loyalist controlled and in several surrounding areas, loyalists were the majority. Adams wrote, New York is “the key to whole continent.” General Lee, by Washington’s request, put together a detailed proposal for occupying New York and the surrounding area. In February, Lee left following a route through Rhode Island and Connecticut, where additional troops from Connecticut were added. After arriving in New York, troops from New Jersey joined and all begin building the defenses. Washington left Boston riding in a luxury carriage on April 4 with his army. They arrived in New York on April 13. Lee’s tactical defense of New York included placing troops on the western end of Long Island behind redoubts, forts in Long Island, and fortifications across the East River in Manhattan. This arrangement created several necessary places where the enemy would face severe cross-fire. The idea was to make the British pay dearly in loses. But, defending from Long Island meant crossing the East River. Until reassigned to the south in March, Lee’s forces worked on the defenses. Lord Stirling replaced Lee and continued. When Washington arrived about a half of the defense were finished leaving him worried. Douglas Freeman added, “In restless, divided New York the soldiers were subjected to temptations different from those they had faced in small New England villages. . . Many of the soldiers went to the dives with the result that venereal disease was prevalent…There were, too, numerous cases of desertion and some instances of drunkenness, combined with so much disorder…” The Army also suffered from the ordinary military diseases of dysentery, hunger, and flues. Washington began moving troops on Long Island during May. They would add several more forts for protecting the main fort, Fort Stirling. Several areas of high ground including Gowan Heights and Brooklyn Heights don western Long Island. Between the highlands are several passes, forded by multiple roads, Gowanus Road, Flatbush Road, and Bedford Road. The American's believe that the British would attack along the Flatbush, thus left Jamaica Pass, one much further to the East, unprotected on the day of the battle. In finishing their defense, the Americans placed cannons at Fort George, Governors Island, and Whitehall Dock with hopes of deterring the English warships from sailing north along the East River, and blockading the Americans. To the west, Fort Constitution and Fort Washington were built along the banks of the Hudson intended to stop British ships from pinning the Americans. Three Generals, Stirling, Sullivan, and Putnam lead. June 9, 1776, British ships left Halifax heading for New York’s Bay. Forty-five ships arrived on the 29th and dropped anchor near Staten Island. By the next week, 130 British ships anchored in the harbor, command by Admiral Richard Howe. The United States Congress declared Independence on July 2, the news reaching Washington on the 6th. The General marched the troops into the Commons and had the Declaration read to them. A mob formed, tore down the Statue of the King from which musket balls were made. The Phoenix and Rose, two English Warships sailed up the Hudson passing unscathed several Continental batteries on the 12th of July anchoring at Tarrytown. Their purposes were to hinder aid from crossing the Hudson into New York. The only casualties of the day came when a cannon crew overloaded their shot causing the cannon to explode. Six Americans died, zero British. The vulnerability of Lee’s plan appeared. On the 13th, General Howe sent a letter requesting surrender to George Washington, Esq. through a currier Philip Brown. The General’s staff rejected the letter as it refused to recognize the General’s rank. Joseph Reed, one of Washington’s staff, answered simply “no one in the army of that address.” Howe sent another letter on the 16th addressing it George Washington, Esq. etc. etc.. Again the Americans refused receipt. Finally Howe purposed a face to face meeting with which Washington agreed. On the 20th, Howe sent an adjutant, Colonel James Patterson, who explained that he came with powers to grant pardons. Washington famously answered, "Those who have committed no fault want no pardon." Patterson left. A stage for war was set. It would be long. Over the next month, hundreds of British ships arrived. On August 1, 45 ships arrived with Clinton and Howe. In all, over 400 enemy ships were in the New York harbor with 32,000 well-trained, well-feed, well-armed troops. This was the largest invasion force ever assembled in the world. The King was obviously serious. With the American’s facing such a large force, Washington became uncertain of whether the attack would be on Manhattan or Long Island. The uncertainly forced Washington into a fatal mistake, he split his troops leaving half on Manhattan and moving half to Long Island. Unlike the English, the 18,000 American’s were ill feed, under armed and untrained. Yet, they held the high ground, or at least they thought they did. | ||||

|

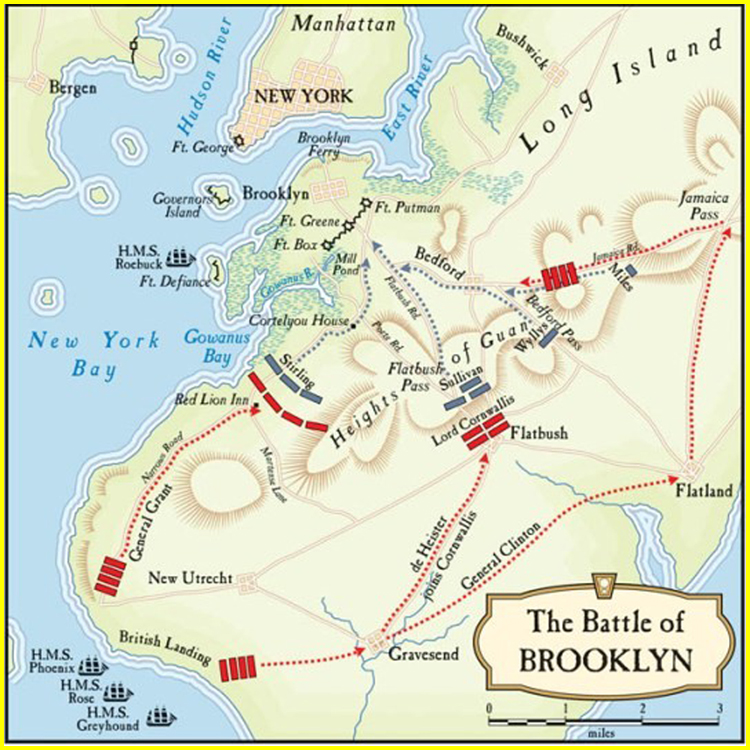

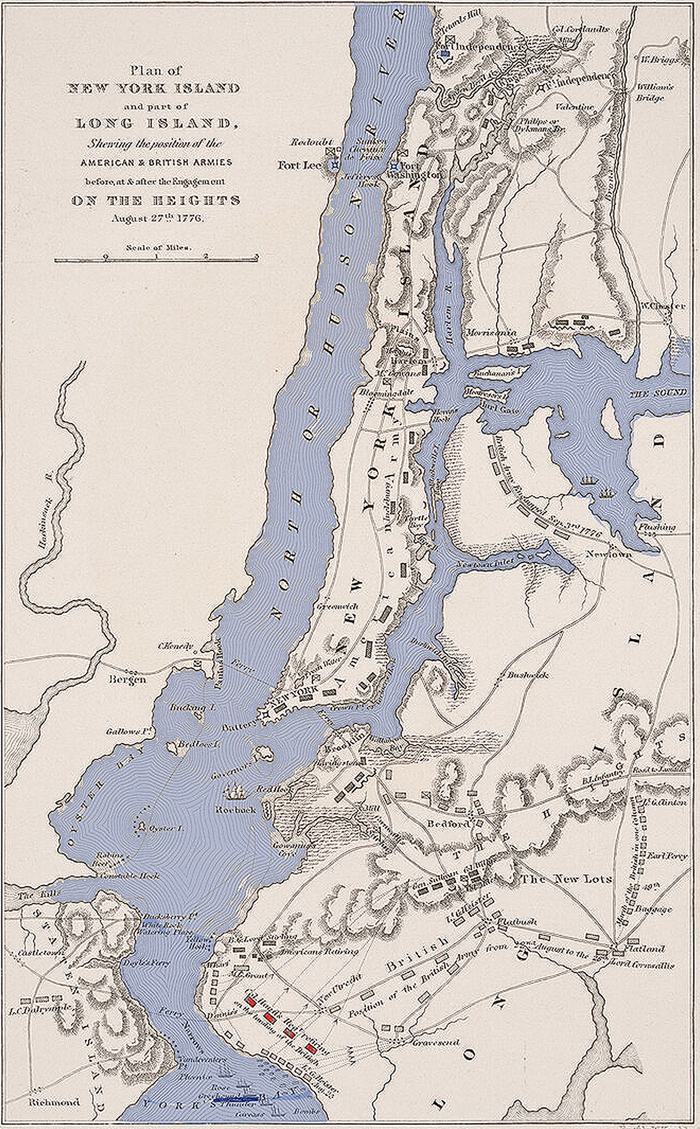

The weather on the 21th of August was stormy, heavy rain fell, deadly lightening cracked. Early in the morning of the 22nd, an advanced guard of 4,000 British landed on Long Island, quickly took control of the resistance and marched toward Flatbush. By 8:00, another 4,000 landed. By noon, 15,000 British were on Long Island. Washington received an inaccurate report about the number of troops landed. They reported only 8,000 leaving Washington firmly convinced Long Island was the ploy. On the 24th, the English added 5,000 Hessians.

Between the 22nd and 26th, Clinton, with the help of local Tories, devised a plan and convinced his superiors to follow through Jamaica Pass an unguarded a path for surrounding the Americans. At 9 PM on the 26th, a force of 10,000 silently marched, campfires around Flatbush still burning. Only the commanders knew the destination, marching east, then north to Howard’s Tavern. Clinton took the owner William Howard prisoner, forcing him and his son to guide the British. By 9:00 AM on the 27th, Clinton was positioned north and east of the American front lines and in between their two main defenses. |

William Howard Jr. describes meeting General Howe: “It was about 2 o’clock in the morning of the 27th of August that I was awakened by seeing a soldier at the side of my bed. I got up and dressed and went down to the barroom, where I saw my father standing in one corner with three British soldiers before him with muskets and bayonets fixed. The army was then lying in the field in front of the house ...General Howe and another officer were in the barroom. General Howe wore a camlet cloak over his regimentals. After asking for a glass of liquor from the bar, which was given him, he entered into familiar conversation with my father, and among other things said, ‘I must have some one of you to show me over the Rockaway Path around the pass.’ “My father replied, ‘We belong to the other side, General, and can’t serve you against our duty.’ General Howe replied, ‘That is alright; stick to your country, or stick to your principles, but Howard, you are my prisoner and must guide my men over the hill.’ My father made some further objection, but was silenced by the general, who said, ‘You have no alternative. If you refuse I shall shoot you through the head." | |||

|

At around 11 PM on the 26th, the Battle began. American’s, under Stirling, attacked British troops moving toward them along Gowanus Road. During the night and early morning, Stirling’s troops held their ground and at times attacked believing they were winning. Unknown to them was the precarious location of Clinton in their rear and to the east. At 9:00 AM, Clinton shot two cannons, the prearranged signal for the Hessians to attach Sullivan from the front of Battle Pass. While the frontal attacked begin, Clinton quickly attacked their rear rolling up the American lines. Sullivan managed to hold off the British long enough for most of his troops to evacuate to Brooklyn. He was eventually captured. With the center collapsed, the Hessians turned west in attack of Stirling’s left flank. British General Grant pressed his frontal attack, and Clinton’s troops were approaching from the back. Stirling realized his only escape route lie across the 80 yard wide Gowanus Creek. At Brouwer' Millpond, Stirling ordered his troops to retreat across the pond while he, Major Gist, and 270 of his Maryland troops provide the rearward guard. Multiple times the Maryland troops attacked the larger force at times almost breaking their lines. Considered today as one of the biggest, certainly one of the most famous blunders of war, with the Americans in a full and disorganized retreat, strangely Clinton disengaged. He could have pressed and finished the Americans. Stirling was captured, yet many safely escaped with the exception of the Maryland 400. During the Battle, the American’s suffered 1,100 casualties and 1,000 captured of which half would die on prison ships. British loses were significantly less. Washington exclaimed of the day, “Good God! What brave fellows I must this day lose!” | ||||

|

During the War, thousands of American troops were captured and incarcerated often aboard ships. The King considered them traitors and were therefore not considered nor treated with the respect granted prisoners of war. On the other hand, Washington’s approach was different. The British and Hessian captures experienced being prisoners of war and received reasonable care in spite of the lack of supplies for their own troops. Washington wrote, “Let them have no reason to complain of our copying the brutal example of the British army." |

Over 11,500 Americans died from abuse and starvation while imprisoned on British prison ships anchored near Brooklyn. Bodies of the dead were often dumped overboard or buried in shallow graves along the shores. Sympathetic residences of New York gathered the fallen for proper burial. A small number of prisoners are buried at a memorial, Prison Ship Martyr’s Monument, in Brooklyn. | |||

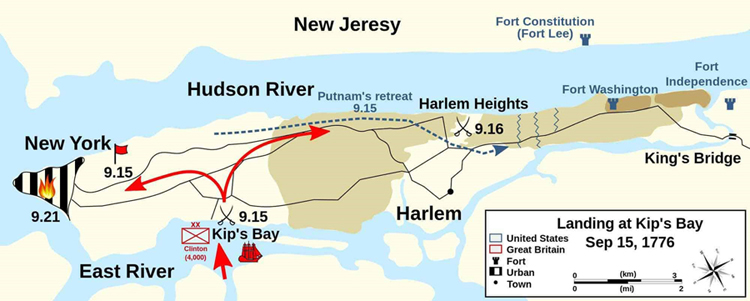

With the Americans barricaded inside Fort Stirling, the British began digging trenches for protection, each trench line reaching closer to the Americans. American reinforcements crossed on the 28th, but the fact remained that the Americans were trapped between the British Infantry in front, the East River to their back with British Warships waiting to seal the deal.  On the afternoon of the 28th, a heavy storm hit the island. Temperatures dropped, heavy rain fell extinguishing campfires, damping gun powder, forcing a natural truce. By evening the wind strengthened and changed direction now blowing in from the Northeast, inhibiting movement of British ships from entering the southern entrance of the East River. On the morning of the 29th, Washington woke to see the British intended plans. During the night, they continued building defenses now as close as 600 yards. Heavy cold rain continued. But bitter winds continued to hold the Warships at bay. Wind also kept the war stalemated. For how long the winds would protect, the Americans wondered. At 4 PM, Washington gathered his staff, seeking advice. A unanimous decision to evacuate was made. General Mifflin volunteered himself and his Pennsylvanian troops for rear guard duty. The camp fires were to remain lite. During the evacuation, officers gave strict orders of silence. Soldiers were to refrain for talking. Rag covered wheels silence the movement of cannons. At 7:00 PM, soldiers assembled being falsely instructed to prepare for a night attack. They would not learn their real mission until reaching the shore of the East River. During the day and under “deliberately misleading instructions,” the American General Heath located on York Island [modern day Manhattan] gathered anything that floated believing he would be transporting troops across to Long Island. By 7:00 he was ready. With darkness came the attempts to cross. Stiff, fierce winds prevented passage. The oarsmen could not battle the head winds and rough waters. Near 11:00 PM, General McDougall sent Washington “an urgent message” asking him to cancel the evacuation. Shortly afterward, the air suddenly calmed, then changed direction to the southwest providing the perfect vector for escape. Thousands crossed covered in darkness. Seemly a miracle provided both protection and assistance on the night of the 29th and 30th. This is not the first time that voices in the wind played a role during our early history. Columbus experienced the voice of adversity during the homeward trip. John Smith and Governor Carver experienced both the voices of direction and trial during their voyages to the New World. West felt the voice of wisdom in the storm separating his vessel from the others. Here the Americans found the voices of mercy and protection embedded with relentless difficulties. Under the Cover of Fog With morning upon them, most Americans had crossed, yet thousands still remained on Long Island now completely unguarded and at the mercy of the British. The winds had died; British ships could now move at the advent of light. Strangely with the beginning light, an uncharacteristic early morning summer fog, thick and deafening, settled in on Long Island and the East River. Its muffling effects covered the continuing evacuation. By mid-morning, the last boats safely crossed, Washington in the very last one. The fog did lift, but not until all reached York. With the morning expired, the British began noticing an eerie silence from the direction of the American lines. Only after the fog lifted, did they come to understand that 10,000 Americans had vanished right in front of their eyes. Howe missed the golden opportunity for capturing the American Leaders, the American Army, and ending the war. The message from Long Island, the war would be long. Washington lived to fight another day. Strange weather once again aided the Americans. (Kip's Bay) With the army safely across the East River, decisions regarding the next moves begin. Clearly, the Americans couldn’t stay on York Island (Manhattan) with the British controlling both rivers, the East and Hudson. An escape from New York City began. The main army advanced north to Harlem Heights and Kings Bridge. Putnam remained until the main body had evacuated. The American left an additional 500 of Connecticut militia at Kip’s Bay to guard against British attacks. On Friday the 13th, British ships sailed up the East River making it clear that something was a foot. During the night of the 14th-15th, British troop and war ships moved into Kip’s Bay. At 10:00 AM, a blistering and deafening cannonade opened against the breastwork defense of the American. By day’s end, 9000 Regulars came ashore and in short order sent the 500 Connecticut defenders on a pell-mell retreat. Washington watched in horror from Harlem Heights. Quickly he rode south desperately

Battles Along the Hudson With the American forces in retreat, British military strategists continued pursuing Washington and the troops trying to capture them and end the war. Many battles were fought along the escape route shown above.

In early September, circumstances left the Army wondering what to do with New York after the inevitable evacuation. Troops once loyal melted away. Washington wrote, “Till of late I had no doubt in my mind of defending this place, nor should I have yet, if the men would do their duty, but this I despair of.” He continued, “If we should be obliged to abandon the town, ought it to stand as winter quarters for the enemy?” Congress resolved no. The British continued their preparation for invading York Island (Manhattan) from Long Island. The American War Councils concluded that the British would come and began moving troops from New York to Harlem Heights, a patch of high ground north of the City. King’s Bridge, the major connection of York Island, was just north of the Heights. Controlling King’s Bridge meant protecting New England; losing King’s Bridge meant opening the door. The morning of the 16th of September opened with American reconnaissance engaging with British advanced pickets. A fire fight ensued, the Americans started to retreat until they heard the British bugling the fox hunt infuriating the Americans. Washington sent reinforcement with hopes of encircling advanced British troops. The British reinforced their lines. The skirmish turned into a full-scale battle by mid-day. The Americans pressed and slowly advanced on the British forcing their move south. It was the first time that the Americans had won against the British. On the 21st and 22nd of September, a fire of unknown cause broke out in New York destroying a large part of the City. Later in October, Washington moved his Army across King’s Bridge to White Plains after learning Howe planned to trap them at the bridge.

Despite the successes at the Heights, Washington continued his retreat understanding that his army wasn’t significant to withstand the enemy. Wanting to avoid a costly frontal attack with the Americans, Howe moved his Army up the East River into Long Island Sound hoping to flank his enemy from the East. Washington left 2000 of his best soldiers at Fort Washington under the command of Greene taking with him the rest into White Plains. Between October 23rd and 28th, the two armies fought several skirmishes. On the American right, Washington had placed 4000 troops on Chatterton’s Hill. The British heavily attacked this position, pushing the Americans eastward. The pinned Americans retreated northward toward North Castle. Again Howe stopped while waiting for reinforcements. On November 1st, the British chased after the army in retreat. Strong winds and heavy rains impeded their chase. Believing the decisive battle was upon them, Washington woke up on the 4th to see Howe in full retreat. The Americans left 11,000 men, mainly New England troops, under the command of Charles Lee in Westchester County with Washington leading a very small army of 2500 into New Jersey. Lee was charged with defending the path to New England. Fort Washington and Fort Lee across the Hudson River from each other were designed to stop enemy warships from traveling the Hudson. The American hope was that these two forts would discourage the Brits from split off New England from the rest of the nation. Washington placed General Nathanael Greene in charge of the defenses. Colonel Robert Magaw, the fort’s garrison commander, managed the garrison. It was Greene’s choice on whether to fight or retreat once the enemy arrived. After much consultation, Greene decided to defend. On November 16th, 3000 Regulars attack from the south and 8000 attacked from the east and north. By 3:00, the stronger larger British forces pinned the Americans inside the breastworks forcing Magaw to surrender almost 3000 troops a far greater number than at Brooklyn Heights. This finished Washington in New York forcing the Americans to begin a long and hardship retreat one that ended in eastern Pennsylvania. With defeat upon defeat, even Washington’s closest friend, Joseph Reed, wrote a treasonous letter to General Lee about Washington’s lack of military capabilities. The daylight darkened without a line of sight toward victory. [Return to Top of the Page] |

||||