Part II Over the next two months, weather again aided the beleaguered army, both with defense and offense. The aid came with suffering that tried their souls. Before leaving New York, Washington divided his army leaving the largest group of 7,000 with General Lee. Lee was to stay on the East side of the Hudson guarding the access to New England. Once across the Hudson River at Peekskill on November 12th, Washington headed south into New Jersey. Washington spent two days conferring with General Greene about whether to fight at Fort Washington or abandoned it. The results discussed previously ended in disaster. With Fort Washington lost, Washington's small army headed south once again in retreat on November 21st. Trying to use Acquackanonk point on the Passaic River as a natural defense, the march continued for five miles, then continued to Newark experiencing heavy rain creating muddy conditions along the narrow roads. With shoeless men nor proper clothed, they suffered immensely. Washington hoped for new recruits while retreating through Jersey. The British believed that it was Washington that held the winning key. For the most part, the British left Lee alone in New York at North Castle, turning rather to chase the marching rags. Americans reached Newark on the 22nd, heavy rains continued resulting in tentless troops exposed to wet and bone chilling cold. Thomas Paine provided moral aid along this retreat penning the Crisis, "These are the times that try men's souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will in this crisis, shirk form the service of their country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman." Cornwallis and his band of 10,000 left on the 25th after the rains stopped. But the heavy wagons, and equipment mired in the mud slowing travel. The English arrived three days later at Newark only to find it empty, Washington traveled on to Brunswick, the town at which Cornwallis had been ordered a stop. At Brunswick on the 29th, Lord Sullivan and 1,000 volunteers joined Washington. On December 1st, with Washington on one side of the Raritan and Cornwallis on the other, cannon from both sides exchanged fire. Having lost 2,000 troops from expiring enlistments, Washington knew running again was his only choice.

During the night, the Americans left leaving the British once again without the fox. On the morning of the 2nd, Washington reached Trenton leaving Stirling with troops at Princeton to guard. The British halted for six days as ordered on the Raritan. On the way across Jersey, British leadership once again offered peace and amnesty of which flocks of once Americans offered loyalty to the King. In early December, the weather turned unseasonably warm. Both armies moved quickly, Washington reaching Trenton overnight. On the day of the 7th, Washington realized how fast the British were coming, ordered all boats destroyed on the east side of the Delaware except those needed to aid the crossing. During the night, the ragged group crossed ending the long arduous march. Rains slowed the heavy loads advancing with the army. Cold weather would aid Washington's army. | ||

| James Monroe wrote this of General Washington, (again taking a quote from 1776), "I saw him . . . or rather in its rear, for he was always near the enemy, and his countenance and manner made an impression on me which I can never efface.” | ||

| The Battle of Trenton The weather again changed, this time turning bitterly cold. On December 13, Howe decided to move his troops to New York for the winter. Leaving only a few, scattered outposts along the Delaware, the main British army relocating to the milder coastal areas. A tattered American army-- now significantly reduced in numbers positioned itself on the west bank of the Delaware. What had been an army of 20,000 just a few months before now numbered just 7,000 men when Lee's group finally arrived. | ||

|

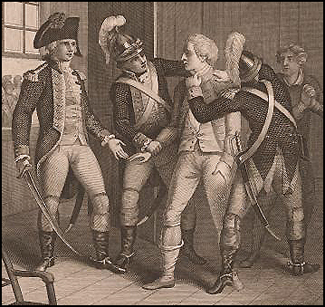

Lee's Capture: Having risked a court-martial for refusing to follow Washington's orders to leave New York, Lee finally broke camp arriving near Morristown, NJ, on the 12th. Wanting comforts, he rode four miles to a tavern for the night taking with him fifteen others for a guard. The next morning, Friday, the thirteenth, Lee ate a leisurely breakfast and was just finishing up a letter to Horatio Gates, when a British scouting party appeared. Within minutes, Lee exited surrendering to the British. Lee's carelessness resulted in his capture. The British were jubilant thinking that they had capture the only capable American military leader. Ultimately losing Lee turned into a blessing for the ragged American army. | |

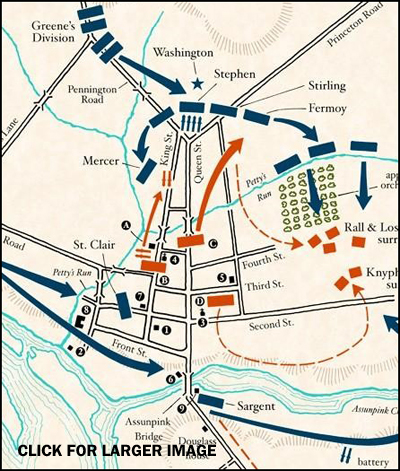

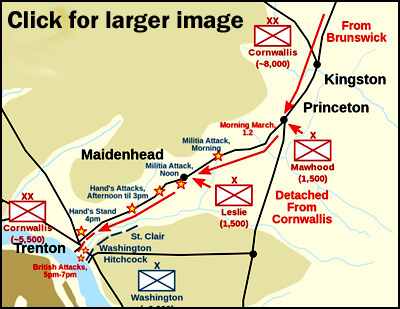

Although the British were evacuating, Washington without adequate intelligence was not certain about their plans. McCullough wrote, "Washington let it be known he was willing to pay for it, at almost any price." In spite of his doubts, Washington's confidence soared. Unsolicited, Joseph Reed sent a letter to Washington dated December 22: "Will it not be possible, my dear General, for our troops or such part of them as can act with to make a diversion or something more at or about Trenton?" Prior to receiving the letter from Reed, the General had already communicated a desire to attack with letters to Congress. As dire as the circumstances seemed, Washington knew he had solid, mature field commanders in Greene, Stirling, and Sullivan. On December 24, 1776, Washington's staff finalized the plan. Washington divided the army into three groups, one crossing at Bristol, another directly crossing at Trenton and a third and largest lead by Washington, accompanied with Greene, Sullivan, and Stirling assisting, at McConkey's Ferry. The intelligence estimated the strength of the Hessians at 2,000-3,000. The plan called for the crossing to be completed by midnight and for Washington's army to reach Trenton under the cover of darkness and then reassemble by 5:00 a,m, on the 26th. On Christmas morning the weather turned stormy-- windy, cold, with heavy rain. At 2:00 p.m. the army began moving from the woods towards the river. Ice covered the now swollen river. Washington and his men crossed early. At 11:00 p.m., the storm strengthened, alternating between rain and snow. The anticipated easy crossing was not completed until 3:00 a.m. on the 26th. What Washington did not know was the other two units failed to cross -- his division stood alone. The British Commander in Trenton, Johann Rall, remained on high alert and Christmas Night was no different. While there were no drunken parties, some troops were more relaxed as they recovered from holiday celebrations. Through their intensive espionage, the British had learned the Americans were coming and were well prepared-- until a group of Virginians unexpectedly attacked in the early morning hours. They were seeking revenge for some poaching done by British troops few days earlier. The Hessians mistakenly thought this was the American attack and let down their guard. Now knowing he and his men marched alone, Washington continued. The General rode among the ranks suffering in the cold often force to shake the weakened and tired who otherwise would have frozen to death. At sunrise on the 26th, the Americans still had not reached Trenton. The element of surprise Washington planned seemed fading with the arriving early morning lights. In Being George Washington, Glen Beck wrote, "He stared toward the town in the distance, or at least where the town should have been. He could see nothing. Another storm had commenced, and it was historic. The sleet and snow filled the air completely blinding and deadened all sound…. The storms other benefit: the enemy advanced sentries had been forced inside." Miraculously, the Americans still found help in surprising the Hessians. The help once again came, bitter cold; it tried shoddy, ill-dressed mostly shoeless troops. It protected; but it didn't ease suffering. Greene's troops attacked first, concentrating on the outer perimeter. After forcing a Hessian retreat, they entered the town with Sullivan's troops alongside. The band and drums of the Hessians continued to play loudly, often drowning out orders from their superiors. The ensuing chaos divided the Hessians. Knox had carefully positioned and then fired cannons at the top of both King and Queen Street. The British reacted to the cannon fire and raced outside to retaliate--only to find that the increasingly heavy snow and sleet had rendered their powder completely ineffective. The British scattered into the side streets—and came face-to-face with Stirling's bayonets. A fierce hand-to-hand, house-to-house battle ensued. Rall failed repeatedly to rally his troops. While leading their retreat, a musket ball struck him. Rall died from his wounds a few days later.  In a remarkable forty-five minutes, the Americans killed twenty-one Hessians, wounded ninety more and captured nine hundred soldiers. Five hundred escaped. Only four Americans were wounded with none killed. The unthinkable and seemingly impossible had happened. Weather, harsh in its descent, yet kind in its effect, altered the final outcome. In a matter of days by word-of-mouth, fast horse and newspapers, the good news spread. Congress wrote, "" It appears to us that you[r] attack on Trenton was [a] success beyond expectation." During the last days of December, Washington had decided to attack within the region again. American General Cadwalader crossed into New Jersey thinking Washington was still in Jersey. With Washington and Greene, Sullivan, and Knox crossing again at McConkey's Ferry, a crossing no easier than the last one, Cadwalader found himself alone. But he remained on the east side gathering supplies, putting together maps, and located enemy positions. His troop's work added valuable information for when the General returned east again. On the 30th, Washington again crossed the Delaware and gathered his troops making an appeal that they stay just a little longer. Many of the enlistments expired on the 1st. He offered each soldier, without any Congressional authority, a ten-dollar bounty to stay. During his first pass in front of the troops, no one stepped forward. As the minutes passed, Washington turned and addressed his troops: "My brave fellows, you have done all I asked you to do, and more than could be reasonably expected, but your country is at stake, you wives, your houses, and all that you hold dear. You have worn yourselves out with fatigues and hardships, but? we know not how to spare you. If you will consent to stay one month longer, you will render that service to the cause of liberty, and to your country, which you can probably never do under any other circumstance." Again, the drums rolled and one by one, the men stepped forward-- until the majority had re-committed. Greene later wrote, "God Almighty, inclined their hearts to listen to the proposal and they engaged anew." Once word reached William Howei n Trenton, he immediately canceled Cornwallis's leave and sent him with 8,000 troops to Princeton. They arrived on January 1, 1777. Cornwallis left some troops in Princeton, and began the march toward Trenton. A sudden winter thaw hit, significantly impacting their movement. The heavy wagons and sloppy roads and gun fire from forward American troops slowed the progress such that the Regulars didn't arrive in Trenton until dusk. American cannon fired on Trenton holding the British at bay. Cornwallis tried three times to cross the bridge at Assunpink Creek being repelled. With darkness now fully enveloping the landscape, Cornwallis abandoned the battle, not wanting to risk heavy casualties from fighting in the dark. His staff warned him  that Washington might silently slip away in the dark. that Washington might silently slip away in the dark.During the night, the British lit no fires, slept on frozen ground hoping to secretly observe American movement. But Washington intentionally left fires burning, attended by a few soldiers, and departed - moving his troops to the British rear at Princeton. Again, strange weather aided the Americans. While during the day before a sudden thaw slowed the British, this night a quick and sudden hard freeze assisted the American army's march to Princeton. Washington used the "backroads" in his travel avoiding contact with the enemy. By daybreak, a fierce fifteen-minute battle broke out at Clarke's Farm ending in a hasty British retreat—some troops to Trenton and others to Brunswick. General Hugh Mercer, an American General and one of Washington's favorites, found himself surrounded by the enemy, his troops having retreated during the firefight. From a distance, Washington observed what was unfolding and immediately rode fast and hard into the battle urging his troops onward. When the British saw a man on a horse approaching, all turned and fired upon him. When the dust cleared, they were astounded to see the General standing on his horse completely unscathed. Witnessing this, one young officer later wrote of Washington, "I shall never forget what I felt. . .when I saw him brave all the dangers of the field and his important life hanging as it were by a single hair with a thousand deaths flying around him. Believe me, I thought not of myself." After the battle at Princeton the American army, weakened to near exhaustion, retreated to Morristown, New Jersey for the winter. A Pennsylvania newspaper article believed that had this experience occurred during a time when idolatry was practiced, Washington would have been revered as God. The winter had culminated with the Americans winning two stunning battles. David McCullough wrote, "Trenton was the first great cause for hope." | ||

|

General Hugh Mercer, one of Washington’s favorite senior officers and a member of his staff, continually tried to emulate Washington’s innate gift for leadership. He did so in both dress and style. As the Battle of Princeton progressed, Mercer did not retreat and steadfastly urged his men onward. When the British saw him coming, they assumed because of his dress and mannerisms, it was Washington. They trapped him and demanded his surrender. When he refused, the British bayoneted him seven times and left him for dead thinking they had cornered and killed the great General Washington. A few days later, Mercer died from his wounds. Mercer County, New Jersey was named in his honor | |

|

In 1775, Thomas Paine wrote "Common Sense", a simplified discussion of the American cause. Its effect was immense—It remains to this day the best-selling publication in American history. The simple literary style made it easy-to-read. It contains Paine's now-famous words: "The cause of America is in a great measure the

cause of all mankind."

During the Revolutionary War, Paine wrote a series of thirteen pamphlets entitled "The American Crisis." The first began with these familiar words: "These are the times that try men's souls: The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands by it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman." Of Paine's writing, John Adams wrote, "Without the pen of the author of Common Sense, the sword of Washington would have been raised in vain." |

| |

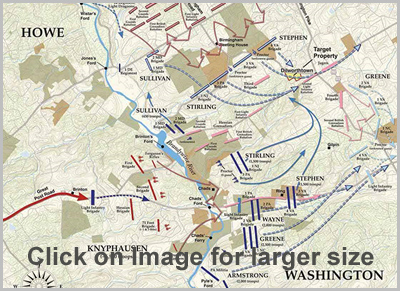

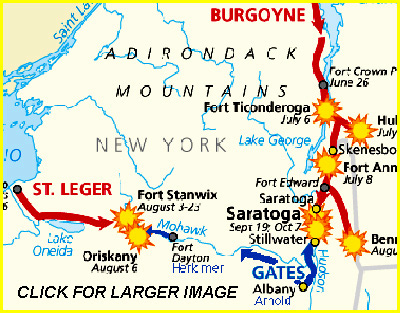

During the winter of 1777 at Morristown, smallpox, fatigue, and a growing lack of supplies plagued the rapidly dwindling American army of 3,000. If the British chose to fight, the cause would have been easily destroyed. Cornwallis chose rather to protect Brunswick where massive amounts of supplies and a war chest resided. He worried that Washington might somehow sneak away this treasure-trove. In the spring, the British attempted several forays up the Raritan River, all miraculously driven back by a woefully weakened army. Washington express thanks “for blessings of a benevolent Providence hovering over his fragmented forces.” During the winter of 1777 at Morristown, smallpox, fatigue, and a growing lack of supplies plagued the rapidly dwindling American army of 3,000. If the British chose to fight, the cause would have been easily destroyed. Cornwallis chose rather to protect Brunswick where massive amounts of supplies and a war chest resided. He worried that Washington might somehow sneak away this treasure-trove. In the spring, the British attempted several forays up the Raritan River, all miraculously driven back by a woefully weakened army. Washington express thanks “for blessings of a benevolent Providence hovering over his fragmented forces.”Suddenly in the early summer, the English disengaged returning to New York. The Americans learned shortly that the British were planning to sail, then march north toward Saratoga, New York to meet British troops moving south from Canada, a plan which would have split the rebellion. On July 24th, Howe set sail not north, but out to sea with 15,000 troops in 250 ships. The Howe and Howe command had changed its mind about supporting Johnny Burgoyne's movement from Canada. Burgoyne was now on his own, a situation that proved fatal. During this uncertainty created by the abrupt British repositioning, a young 19-year-old Frenchman, Marquis de Lafayette, arrived in the Americas with 22,000 guns and other badly needed supplies. Within a few weeks, new recruits appeared greatly bolstering both Washington's forces and General Horatio Gate's, the American commander in northern New York. At first, intelligence believed that the English were heading south. Washington pursued. In early September, word came that the British had sailed up the Chesapeake and now marching toward Philadelphia. On the morning of September 11th, the Americans and British met along Brandywine  Creek. A fierce battle began at Chad's Ford. Howe had split his troops the second unit, the major force, heading toward Trimbles Ford then Jefferies both unprotected crossings, a few miles from Chads. In haste, Washington split his troops sending several thousand under Sullivan's command toward the English heading at the American right flank. When Sullivan could not locate the enemy, a confused Washington ordered a halt. At 2:00 p.m. on the 11th, Washington received word of the British crossing heading toward Washington's rear and right flank. He hurried more reinforcements. Both sides fought valiantly, but the much larger British force overwhelmed the Americans. Casualties were high: the Americans, 1,200, the British, 600. Another Washington defeat. With the loss, Congress force evacuated to York. Creek. A fierce battle began at Chad's Ford. Howe had split his troops the second unit, the major force, heading toward Trimbles Ford then Jefferies both unprotected crossings, a few miles from Chads. In haste, Washington split his troops sending several thousand under Sullivan's command toward the English heading at the American right flank. When Sullivan could not locate the enemy, a confused Washington ordered a halt. At 2:00 p.m. on the 11th, Washington received word of the British crossing heading toward Washington's rear and right flank. He hurried more reinforcements. Both sides fought valiantly, but the much larger British force overwhelmed the Americans. Casualties were high: the Americans, 1,200, the British, 600. Another Washington defeat. With the loss, Congress force evacuated to York. American troops moved north of Philadelphia to Paoli, Pennsylvania some days later. On the night of September 20th, the British under Mad Dog Wayne night attacked the Americans killing and wounding hundreds. On the September 26th, the British marched into Philadelphia where they made their winter camp. On October 3rd, Washington, bolstered by thousands of reinforcements attacked a smaller British contingent at Germantown. The Americans initially caught the British off-guard; but they soon regained their equilibrium and fiercely countered, sending the Americans into a hasty retreat. Again, another Washington defeat. Still, Washington found great reasons for hope writing this strange note, "a superintending Providence is ordering everything for the best and that in due time all will end well." It was as if Washington knew the outcome. While Howe and Clinton moved south from New York -- General Burgoyne and 8,000 troops headed south from Canada -- mistakenly believing they would rendezvous with Sir William Howe's 15,000 in Albany -- a strategic move which would have geographically divided and demoralized the struggling young nation. By July, "Gentleman" Burgoyne had reclaimed lightly defended Fort Ticonderoga. Thinking the Americans could better defend a water route, Burgoyne choose to march by land toward the strategic Fort Edward, New York. The un-fooled Americans filled the roads with fallen trees and burned bridges, slowing the enemy's progress. The British managed just 23 miles in twenty days and reached Fort Edwards on July 29, 1777. More importantly, the Brits were now completely exhausted, supplies dangerously low. In the middle of August, Burgoyne sent two different parties, one under Baum and another under Breymann, toward the Connecticut River valley to plunder for food and supplies. Meanwhile, on August 16th, the American General John Stark disguised a portion of his troops as Hessians and stealthily moved them through the Hessians ranks to their rear and flank. Once they had the Hessians surrounded, Stark yelled, ". . .You must beat them—or Molly Stark is a widow tonight!" A fierce battle near Bennington, Vermont ensued with all but nine Hessians killed or captured. When the battle ended around noon, Breymann and his reinforcements arrived. Strangely, American reinforcements arrived at the same time. The battle began anew; the British were again defeated. To the west of the main British force, a British commander, Barry St. Leger tried to lay siege to Fort Stanwix, a critical location for defending the American western flank. American troops, under General  Herkimer, were sent to engage Leger. He and his men were drawn away from the fort to fight the incoming American troops. The British won but suffered terrible casualties.

While heading back to the Fort, General Leger encountered two American Natives, sent by American General Benedict Arnold. Each exaggerated the number of Colonist troops en route and corroborated the other's story. By this time, both the Tory and Native American soldiers within Leger's force had diminished to the point where it left him but one choice, a full retreat. Herkimer, were sent to engage Leger. He and his men were drawn away from the fort to fight the incoming American troops. The British won but suffered terrible casualties.

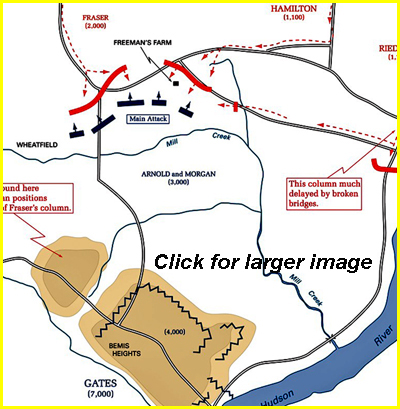

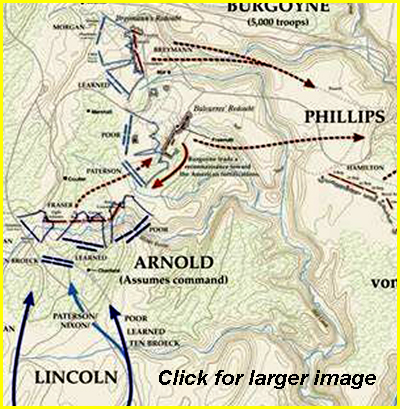

While heading back to the Fort, General Leger encountered two American Natives, sent by American General Benedict Arnold. Each exaggerated the number of Colonist troops en route and corroborated the other's story. By this time, both the Tory and Native American soldiers within Leger's force had diminished to the point where it left him but one choice, a full retreat. Having just learned that Howe wasn't coming, General Burgoyne grew desperate. His isolated situation left no choice but to attack. Seven thousand Americans, under the command of Horatio Gates, dug in at Bemis Heights and waited for the attack from General Burgoyne's 8,000. On September 19th, the main battle erupted. Arnold had rejoined the main American body and desperately petitioned Gates for permission to attack directly. After a heated argument, the consent was grudgingly granted.  Taking Daniel Morgan and his unit of sharpshooters, Arnold and the Americans attacked at Freeman Farm. The sharpshooters forced the enemy into early retreat; British reinforcements returned fire andthen forced Morgan into retreat. Finding a wooded area, the sharpshooters climbed into the trees and began picking off the British officers and artillery. All but a few fell. Arnold recognized a key opportunity to send the British into full retreat, but Gates refused to send additional reinforcements. For two weeks, Gates and Arnold argued bitterly over Gates taking credit for the initial victory at Freeman Farm. Taking Daniel Morgan and his unit of sharpshooters, Arnold and the Americans attacked at Freeman Farm. The sharpshooters forced the enemy into early retreat; British reinforcements returned fire andthen forced Morgan into retreat. Finding a wooded area, the sharpshooters climbed into the trees and began picking off the British officers and artillery. All but a few fell. Arnold recognized a key opportunity to send the British into full retreat, but Gates refused to send additional reinforcements. For two weeks, Gates and Arnold argued bitterly over Gates taking credit for the initial victory at Freeman Farm. On October 7th, the British began a final attack. Gates flatly refused Arnold's request to lead the troops and instead sent two other senior officers, Daniel Morgan, and Enoch Poor. Arnold was furious. The Americans pressed hard but the British did not fold nor retreat. Suddenly, a very frustrated Arnold bolted from his haven at Bemis Heights and without orders rode into battle taking command of the entire army to the cheering of the troops.  Arnold rallied first against a Hessian line folding it. Then he ordered Morgan to take out a British senior officer, Simon Fraser. The British retreated. Arnold then circled around the British and led the Americans into attack. Quickly, the Americans drove the enemy from their stronghold. Within three days, the Americans completely surrounded the British, and forced a complete surrender on October 17, 1777. The Americans had won a stunning victory at Saratoga. Arnold was the hero; Gates arrogantly took the credit. This victory convinced the French to enter and assist the American cause. Not enough importance can be said about the importance of Washington's army holding off Howe in Pennsylvania for this needed victory to materialize. Arnold rallied first against a Hessian line folding it. Then he ordered Morgan to take out a British senior officer, Simon Fraser. The British retreated. Arnold then circled around the British and led the Americans into attack. Quickly, the Americans drove the enemy from their stronghold. Within three days, the Americans completely surrounded the British, and forced a complete surrender on October 17, 1777. The Americans had won a stunning victory at Saratoga. Arnold was the hero; Gates arrogantly took the credit. This victory convinced the French to enter and assist the American cause. Not enough importance can be said about the importance of Washington's army holding off Howe in Pennsylvania for this needed victory to materialize. With Washington losing at Brandywine and Germantown, Congress once again began to question General's competence. By the winter of 1777-78, only two of the original Continental Congress members still remained. A "whisper campaign" for Gates to replace Washington began in earnest. General Thomas Conway wrote of Washington's grave incompetence. Lee, as a prisoner, wrote Congress of the same. Thomas Mifflin, a former member of Washington's staff, convinced Congress to form a war advisory board, placing Mifflin, Gates, and Conway on the board and above Washington in rank. When word spread that an effort to remove Washington was under way, the troops rebelled. In the spring of 1778, Congress finally reconfirmed their support for the stalwart General. After Germantown, Washington moved the army of 10,000 from place to place and on December 19th finally settled on the high ground of Valley Forge for their winter encampment, far enough from Philadelphia to prevent surprise attacks, while offering protection for Congress. From Valley Forge, the Continental's could still watch the enemy. Upon arrival, Washington immediately instructed each army unit where to make camp. In preparation for the long winter ahead, the General had carefully inspected maps and conferred with locals. The overall weather during the winter of 1777-78 was moderate. However, the troops endured two bitter cold spells -- one near the end of December and the other in early February. The weather in between was milder. The deepest snow of the winter occurred while the troops were marching into the Forge. And the erratic temperatures significantly increased the susceptibility of the soldiers. The cold weakened them, and the unusual warmth fostered an environment ripe for disease. They came to Valley Forge without shoes, clothes, or food. Their quartermaster, Thomas Mifflin, had all but ceased to function earlier in 1777. By the time the army reached the Forge, he had asked Congress for an official release. Eventually Washington demanded a replacement and General Greene reluctantly filled this role from March 1778-August 1780. To procure goods while at Valley Forge, Washington empowered General Greene to send his soldiers into the countryside confiscating necessary supplies -- leaving behind promissory notes. The overinflated wartime market often demanded prices a thousand percent above market, prices only the well-heeled British Regulars could afford. Of their conditions, one soldier wrote, "Poor food—hard lodging—Cold Weather—fatigue—Nasty Cloaths—nasty Cookery—Vomit half my time—smoak'd out of my senses—the Devil's in it—I can't Endure it—Why are we sent here to starve and freeze…?" General Nathanial Greene said, he "never saw the army so near dissolving. . . " During the next few months, 2,000 died from disease or exposure, 3,000 deserted and went looking for food from the enemy; and 200 officers simply left their posts.

While at Valley Forge, Washington continued to plead for heavenly intervention. His grandson later wrote, "Throughout the war, as it was understood in his military family, he gave a part of every day to private prayer. . ." With France deciding to join the struggling American cause against their common enemy, England, American spirits buoyed. With this support came Friedrich Wilhelm Ludolf Gerhard Augustin Baron von Steuben, a man who had served under the Prussian leader, Frederick the Great. Von Steuben came to America with honorable intentions. Washington quickly appointed him to train the ragged army. His unique style proved effective. He personally trained troops in small groups—a technique unheard of at that time. His tyrannical approach—which included a lot of swearing--made the men laugh. He taught marching, maneuvering and most importantly, the use of a bayonet. The American army emerged re-energized, a formidable army, a true fighting machine. This opportunity offered, likely unintended, by the British, gave the Americans ample opportunity to fix itself. It wasn't easy; it contained suffering beyond our imagination; the Americans weren't deterred. Looking forward, the British paid. Washington understood that the new British Commander, Sir Henry Clinton, at Philadelphia would not stay. The American army was well-trained and now large enough to isolate and force surrender. The isolated city proved a worthless military prize. The two armies were now of equal size and strength numbering about 10,000. In May, Washington sent troops towards Philadelphia from time-to-time to test the British resolve. Finally, at sunrise on June 18th, Clinton began his slow march to New York. Washington wondered by which route the British would travel, southeast to the Chesapeake, by land through New Jersey or by land and sea directly east. Clinton chose crossing New Jersey. Obstacles such as purposefully destroyed bridges, fallen trees across roads, resulted in the heavy artillery and supply wagons to fall dangerously behind.

Washington knew this British retreat presented a pivotal opportunity to end the war. The divided American War Council convened to discuss plans. Some sided with Washington, others were in favor of attacking the rear with a smaller force, and some favored no attack. Finally, the Council decided to send a small force dividing it between the British left flank and rear. But on June 24th, American intelligence recommended a large attack force. On June 25th, the American army moved toward an area in Monmouth County, New Jersey. Washington offered General Charles Lee -- having been exchanged by the British for other officers held by the American's -- command. What Washington didn't know is that Lee had been negotiating with the English to help broker peace by surrendering the Americans with conditions. Lee, though initially against this move, finally accepted. Approximately 2,000 American soldiers under Lee headed for Monmouth County Court House and positioned themselves on the high ground. Washington and Greene with their 8,000 followed three miles behind. On the morning of June 28th, the British began to fight in earnest. Recognizing the American disadvantage, Lee quickly ordered a general retreat, then a pell-mell run. Not far on the west side of Freehold, Lee and his troops encountered Washington. Uncharacteristically, Washington was livid with Lee for not standing fast until the rest of the army had reached him. Lee made every possible excuse. While the General normally kept his reprimands private, Washington began publicly swearing at Lee. One present wrote that it was one of the finest "cussing-outs" he had ever heard, saying, "Till the leaves shook on the trees." In a rare moment of departure from his even-tempered disposition, Washington made his point. Leaving Lee, Washington hurried into battle quickly reorganizing the troops. Of this reorganization, Greene wrote, "The commander and chief was everywhere, his presence gave Spirit and Confidence." On this particularly hot summer day, both sides fought valiantly, the Americans holding the upper hand. Darkness settled in before the task could be completed. The British lost approximately 1,200; the Americans, approximately 300. A few hundred more on both sides died of heat exhaustion. Many lost their horses to heat stroke including Washington and Hamilton. Over five hundred British troops deserted that day joining the Americans. Washington was extremely pleased with the performance of his newly trained army. At dusk, both sides retired for the night. Von Steuben gladly admired his handwork from the rear. Using a Washington tactic, Clinton secretly forced marched his troops from Monmouth during the darkness, escaping to New York. The Americans lost a chance at victory. The Government formally disciplined Lee, who voluntarily and permanently severed himself from the American army. Lee died in 1782. After Monmouth, Washington cornered the British in New York through his continued presences in New Jersey. Yorktown would be the next and final northern battle. But beforehand, the Americans again found themselves spending a difficult winter even the most difficult winter of the war near Morristown, New Jersey. Valley Forge had its cold spells, but the winter of 1779-1780, according to the best records, was the coldest in 400 years. For the first time in recorded history, the rivers in southern Virginia froze over, as did the upper Chesapeake Bay. In January, the daily high in Philadelphia rose above freezing once. The troops arrived in Morristown on the 2nd of December and immediately fell six hundred acres of trees to build a thousand cabins. During this winter, the snow never melted rather piled higher. General Nathanael Greene still carried the commissary responsibility. By early January, the army found itself in the usual status being without food, clothing, and other supplies. Washington requested that the New Jersey farmers near provide meat, wheat, and other supplies. They did and saved the army for another day. By March, provisions once again ran low. Again, the troops suffered. In late May, the soldiers mutinied only put down with great difficulty. The problem went far beyond cold weather. There were supplies in the area, often plenty. It was about the money, the American money; it was worthless. Washington would later write, "a wagon load of money will scarcely purchase a wagon load of supplies. The British bought gold and other forms of hard money. The Americans, nothing but paper backed by a government of uncertain destiny. Through the whole summer, supply issues haunted the army. The Critical Years ended. With the help of timely weather patterns, Divine Providence, and a willingness to endure, the Americans survived forcing the English in the north into corners. Money had gone bad, but support continued to increase. Hope was abounded. | ||

|

Several descriptive quotes from Emerging Revolutionary War Era describe the winter's plight,

"The winter that year was bad. . . . New Jersey had twenty-six snowstorms and six of those were blizzards! Every saltwater inlet from North Carolina to Canada froze over completely. In fact, New York Harbor froze over with ice so thick that British soldiers were able to march from Manhattan to Staten Island." "one surgeon recorded that "we experienced one of the most tremendous snowstorms ever remembered: . . .. When the storm subsided, the snow was from four to six feet deep, obscuring the very traces of the roads by covering fences that lined them." "Even General Washington noted . . .. "The oldest people now living in this Country do not remember so hard a winter as the one we are now emerging from. In a word the severity of the frost exceeded anything of the kind that had ever been experienced in this climate before."" "Yet, instead of the death toll of 2,000 at the Forge, 'only' approximately 100 died at Morristown." | ||

|

[Return to Top of the Page] |

||